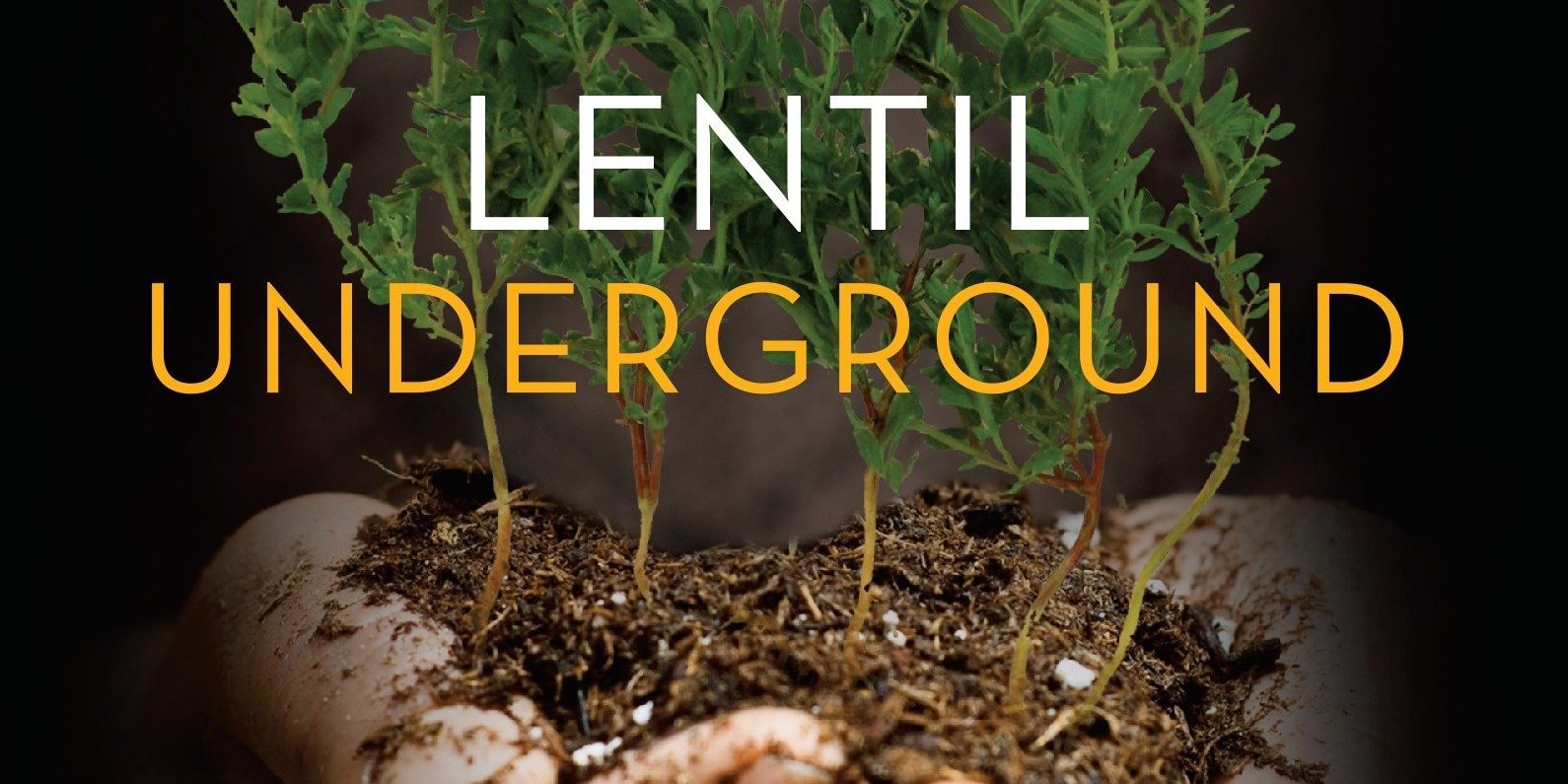

Perhaps part of the answer comes from better knowing my community. It was a wet, late-September morning in the Highwood Mountains when I met Liz Carlisle, eyes shining bright under her pulled-low beanie. Author of Lentil Underground and co-author of Grain by Grain, and Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at UC Santa Barbara, Carlisle focuses on the role of people and communities in sustainable food systems. I was fascinated by this approach because research on sustainability so often focuses on the environment and economy but misses the third pillar: people. In both Lentil Underground and Grain by Grain, Carlisle chronicled the progress made by Montana farmers in harnessing nature to make their land more productive and their communities healthier, all while pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Expanding on her previous two works, Carlisle’s latest book, Healing Grounds: Climate, Justice, and the Deep Roots of Regenerative Farming, began over many discussions around how agricultural practices could trap carbon dioxide. In these, she kept finding that “even people in ‘my community’—the organic proponents—seemed to have widely divergent viewpoints” about the global environmental benefits of healthy soils. Even if individual farmers benefit greatly from carbon-rich soil, do these individual efforts benefit the global atmosphere?

In our conversation, I got to ask Carlisle’s advice on how to handle my struggle for direction as a consumer and aspiring farmer. She empathized: “I wrote this book wanting to find the sense of possibility for myself” about how to take action on climate change. Healing Grounds highlights the stories of producers who are forming deeper relationships with their land. As she worked, Carlisle came to understand how the traditional wisdom which Indigenous communities have developed over thousands of years acts as the bridge to forming those relationships. In relying on these bodies of wisdom, these producers help to intertwine the actions of the individual with those of the community. And, as laughter mixes with her words, it seems clear that she has indeed found her sense of possibility in asking not “What can I do?” but “What can we do?”.

Building soil health offers an analogy to forming these relationships. “Soil” is an ecosystem in which many, many organisms interact. These interactions create an environment which is highly conducive to successful plant life and more-so than any man-made fertilizers. The agricultural community is increasingly interested in how we can best tend to that soil environment, since it will produce the best harvest. Carlisle a lesson to ourselves as well: tending to those around us, akin to our own soil environment, will make our community healthier, and we become healthier as a result. Pursuing that complex, deeper, approach through understanding your land, your farmer, your partners in food answers the question “what can we do?”

At the end of her book, Carlisle shares insights from Native ethnobotanist Stephanie Morningstar. Morningstar sums up the work of the many voices in Healing Grounds: healing—amongst and within individuals, communities, societies, and even with nature—comes from “going back to the land together.” I had the opportunity to ask Carlisle “How can we begin forming those relationships?” “We have a lot of economic relationships in our lives,” Carlisle explained, but, instead of transactions, we might look at those interactions as opportunities for reciprocity.

We may not all be farmers, but we all do have something to share. It may be through growing pandemic gardens and sharing the harvest, buying the “ugly” produce, or sharing what we buy from our farmer with neighbors. As Carlisle describes, giving and receiving is “a way to keep those ‘muscles’ [of reciprocity] active.” In doing so, we have the chance to look at the rest of the world differently, and perhaps we can find solutions to our crises through better understanding our world and one another.

On the Hi-Line, we are in a dire situation. But stories like those in Healing Grounds—examples of people making reciprocity central to their lives and sharing what they have learned—offer hope and advice on how we can better know this land on which we are privileged to work and the people who steward it with us.

About Us

About Us

Vision & Values

Vision & Values

Friends of AERO

Friends of AERO

Our Team

Our Team

Jobs & Board Opportunities

Jobs & Board Opportunities

Montana Food Economy Initiative

Montana Food Economy Initiative

Grassroots Leadership

Grassroots Leadership

Abundant Montana

Abundant Montana

Value-Added Producer Success

Value-Added Producer Success

#FutureGenMT

#FutureGenMT

Downloadables

Downloadables

Videos

Videos

Webinars

Webinars

Get Inspired

Get Inspired

Jane Kile Scholarship

Jane Kile Scholarship

Events

Events

Sun Times

Sun Times

News

News

Success Stories

Success Stories

Expo 2024

Expo 2024

Growing up in the foothills and swamps of South Carolina, Dalton Fulcher was drawn to Montana by its vibrant agricultural communities desiring both to learn from and contribute to their success. He has worked in different aspects of sustainable food systems, from Appalachian ethnobotany to soil microbiology and organic waste management, most recently working in production. Dalton has always been curious about the many ways people relate to the natural world, understanding food and agriculture as vehicles for social and environmental healing.

Growing up in the foothills and swamps of South Carolina, Dalton Fulcher was drawn to Montana by its vibrant agricultural communities desiring both to learn from and contribute to their success. He has worked in different aspects of sustainable food systems, from Appalachian ethnobotany to soil microbiology and organic waste management, most recently working in production. Dalton has always been curious about the many ways people relate to the natural world, understanding food and agriculture as vehicles for social and environmental healing.